Josh Lerner, Co-Executive Director of People Powered, spoke with Meelika Hirmo from Citizen OS about why the future of democracy depends not on constant innovation, but on connecting and strengthening the practices we already have. Lerner challenges the constant pursuit of “the next big thing” in democratic innovation. Instead, he calls for investing in long-term, connected ecosystems of participation that strengthen what already works.

From 16–18 June 2025, as part of the Erasmus+ funded “Democra-SI” project coordinated by Nexes Interculturals (Spain) and involving 22 partners from 12 countries, experts and civil society actors gathered to explore and amplify inclusive democratic narratives across Europe.

In the lead-up to the seminar, Citizen OS—one of the partners of “Democra-SI” and a member of the People Powered network—conducted interviews with international democracy experts to examine how to strengthen democratic participation and address shrinking democratic spaces.

Read the other interview with journalist and professor Xavier Giró here!

As a founder of the global democracy network People Powered, what have you learned from its evolution? Any key lessons or mistakes that stand out?

Josh Lerner: Running participation and democracy programs is hard. Often, it feels like you are the only one facing these obstacles, but many of these challenges are actually shared across different contexts. For example: how do we communicate our work effectively to diverse stakeholders? How do we build support from elected officials and policymakers? How do we engage people both in person and online? How do we measure impact?

We hear very similar concerns from people around the world. One of our key learnings at People Powered is the importance of creating spaces where people can come together to address these shared challenges collaboratively. This collective, ongoing work is essential, more so than launching isolated pilot projects or short-term efforts.

Many civil society groups work project by project. How can we move beyond that, especially when it’s hard to find funding for ongoing work that improves what already exists?

Josh Lerner: Yeah, absolutely. Part of what we try to do is ensure that even when we work on a project, it contributes to something bigger.

We try to structure project work so it contributes to a bigger picture. For instance, a project focused on climate engagement should feed into shared resources and guidance for people globally, offering new insights or techniques as part of a broader program.

Unfortunately, funding often requires projects to be time-limited, but these can still be designed to connect with longer-term international efforts. More broadly, we need to rethink democracy funding — the current approach isn’t delivering lasting results. Anti-democratic actors have been more successful because they invest flexibly and long-term, building infrastructure for political change over decades.

Meanwhile, pro-democracy forces have been doing one-year pilot programmes—and that’s a losing strategy. These short-term, disconnected efforts might produce some results, but they don’t address the root problems. They’re not enough to meet the deeper challenges democracy is facing.

Anti-democratic forces are fast, coordinated, and global. Based on your experience, what should civil society be doing differently to keep up?

Josh Lerner: We need to be able to pursue a few major strategies at the same time. It’s not an either/or situation—we need a both/and approach, focusing on what matters most. Three priorities stand out:

- Defend: There are aspects of current democratic systems worth protecting, though not everything. We need to acknowledge system flaws and the dissatisfaction many feel.

In places where anti-democratic movements are rising, this cynicism is very common. So we need to listen to those concerns and not just respond by saying, “Everything is fine.” We need to defend selectively. - Build Better Systems: Second, we need to build better systems. And we don’t need to start from scratch. This isn’t about constant innovation or chasing crazy new ideas. There are already many effective democratic practices—participatory budgeting, citizens’ assemblies, participatory urban planning, legislative theatre. These approaches work. We need to expand them, connect them, and create systems of democracy that people can believe in and get excited about.

- Imagine the Future: We must envision what democracy should look like in 50 or 100 years — factoring in technological and cultural changes — and start moving toward that vision today, even if the exact outcome is unknown.

Are there any examples from Europe that have personally inspired you?

Josh Lerner: The city of Paris offers an interesting example where various democratic practices are integrated into a broader ecosystem. Paris has a traditional city council but it also introduced participatory budgeting with a significant budget: 100 million euros per year. That’s significant. It’s not a side project.

They have a city-wide citizens’ assembly connected to the budgeting process and able to convene panels on different issues. This multi-layered approach creates more meaningful citizen involvement and a more resilient democratic system. That, to me, is a vision of resilient, dynamic democracy. It’s not perfect—they’re learning as they go—but that’s the only way to learn.

The focus of the seminar “Democra-Si” is narratives and democracy. Can you share an example of a harmful story that has been powerful against democracy—something well done but dangerous?

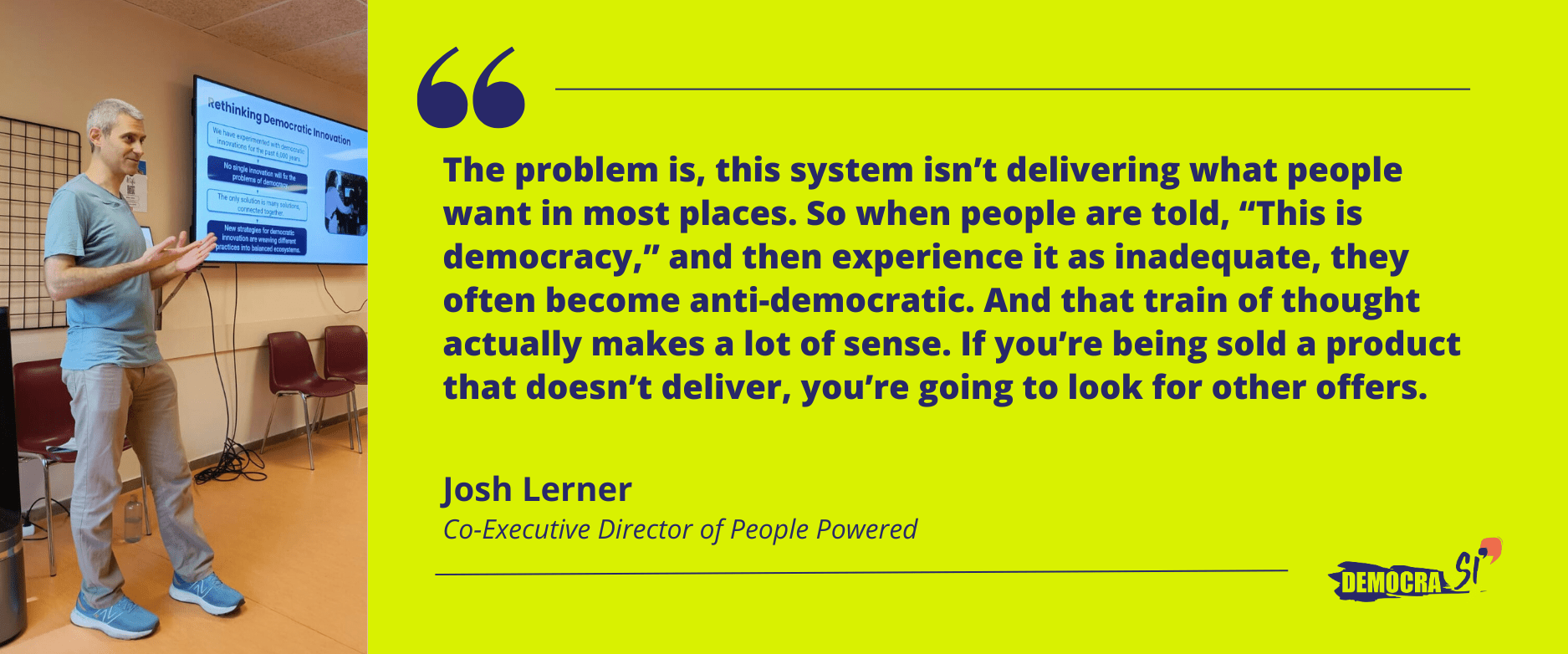

Josh Lerner: What comes to mind isn’t a particularly awful story, but rather the dominant story that, while not evil, is causing a lot of harm. It’s the idea that democracy equals elections. That if you elect your leaders every four years—or however often—then you’ve got democracy. Check the box.

The problem is, this system isn’t delivering what people want in most places. So when people are told, “This is democracy,” and then experience it as inadequate, they often become anti-democratic. And that train of thought actually makes a lot of sense. If you’re being sold a product that doesn’t deliver, you’re going to look for other offers.

People are turning to authoritarianism and autocracy—not because they hate democracy, but because they’re dissatisfied with what they’re told democracy is. So if our story of democracy is just “vote every few years,” we’re actually undermining the broader idea of people having power to make decisions about their lives. That, to me, is what democracy is: rule by the people—not just by elected officials.

Electoral democracy has only dominated the idea of democracy in the past few hundred years. But democratic practices—assemblies, random selection, direct participation—have existed for thousands of years. There are democratic traditions dating back to ancient Mesopotamia.

So this narrow, modern idea of democracy has clouded our vision. It prevents us from seeing what else democracy can be. And it’s weakening support for democracy itself.

Why do people get attracted to autocratic or anti-democratic powers?

Josh Lerner: People do want to be heard and represented. Often, they feel elected officials don’t represent them, and autocratic leaders promise to speak for “the people” and safeguard their interests. This populist rhetoric appeals to those who feel left behind or ignored by the current system.

People don’t necessarily trust empirical research when making these decisions; they are driven by feelings and promises of inclusion and voice.

Could complexity and high demands of participation itself be a barrier for many people?

Josh Lerner: Yes, absolutely. Meaningful participation requires time, energy, skills, and resources many people don’t have, especially if they are struggling with basic survival. The complexity and effort involved can be discouraging.

This is part of why autocracy appeals — it’s simpler and more streamlined. One leader makes decisions, and people don’t have to navigate a complicated system.

But we can and should make participation easier and more accessible through technology and better practices, so people find democratic engagement a more attractive and doable option.

You recently published a white paper exploring the waves of democracy and the idea of democratic ecosystems—also the focus of your talk at the “Democra-SI” seminar. Could you give us a quick teaser? What’s the main idea behind the paper?

Josh Lerner: Yes, it’s called “From Waves to Ecosystems: The Next Stage of Democratic Innovation”.

So we often talk about democratic innovation as something new—we need new things. But if we look back at the history of democracy, we can see that there have been many waves of democratic innovation: from ancient Athens with sortition and direct democracy, to electoral democracy, referenda, town meetings, and participatory approaches in the 1960s, and more recently this deliberative wave.

These waves are exciting—it feels great to be part of a new practice—but they also have disadvantages. They’re competitive, they don’t combine well, and they’re not very sustainable. What I’m seeing now is a shift from focusing on separate waves to building more connected and resilient ecosystems of democracy. The next stage of innovation isn’t about creating something new, but about connecting the practices we already have, strengthening them, and enabling them to support each other.

That’s the most innovative thing—and it goes against the logic of always seeking the new. But if you want to be innovative, don’t just look for the next thing. Look at how to build more resilient, connected ecosystems.