From 16–18 June 2025, the “Democra-SI” seminar in Barcelona, Spain, experts and youth work actors gathered to explore how narratives influence democracy. Meelika Hirmo of Citizen OS interviewed journalist and professor Xavier Giró about the role of media discourse in shaping public perception and democratic potential.

The Erasmus+-funded seminar explores how stories about democracy—and those against it—shape public opinion, policy, and our shared future.

In a conversation with Xavier Giró, we learned that understanding these narratives is key to protecting democratic societies. How do they shape views on freedom, justice, and power? How can we counter rising polarisation, hate speech, and authoritarianism? And how do we challenge anti-democratic discourse?

The answer goes beyond facts and strong communication—it requires empathy and openness to share truthful narratives that connect with people’s real experiences.

What do we mean when we talk about “narratives of democracy”?

Xavier Giró: To be honest, I don’t usually use the term “narratives of democracy.” But if we understand it as storytelling, then yes—it’s key. Humans respond to stories. And in today’s media landscape, there’s a constant stream of messaging, not only from traditional outlets but also from political actors. The far right is especially effective in pushing persuasive stories that blame immigration, feminism, or diversity for society’s problems.

What kind of stories is the far right spreading?

Xavier Giró: Their core message is this: “You’re suffering because of others.” They link unemployment, housing shortages, and social unrest to immigrants, feminist movements, and ethnic or religious diversity. In Spain, for example, unaccompanied migrant minors are labeled “MENAs”—a term now loaded with fear and suspicion. These stories are simple, repeated often, and emotionally charged. Over time, they sink in.

What’s driving the appeal of these stories?

Xavier Giró: Economic crises play a huge role. When people lose jobs, can’t afford rent, or feel insecure, they become more vulnerable to scapegoating. The far right offers a clear, if false, explanation: “It’s the fault of the others.” Unfortunately, even traditional right-wing or moderate parties adopt this language to avoid losing voters. This shifts the whole political spectrum to the right.

Why aren’t democratic or empathetic narratives more popular?

Xavier Giró: Because many people are in real, material hardship. If you’re waiting in a crowded hospital, it’s easy to resent the person next to you, especially if you think they’re “not from here.” Instead of demanding better services, people start competing for what little is available. So yes, we need better discourse—but we also need to address structural inequalities.

Has technology changed something in this regard?

Xavier Giró: These new technologies have the potential to amplify what is already dysfunctional—isolated incidents of criminality, for example. Instead of promoting solidarity, they often fuel division and hate. Unlike the era of large media outlets that influenced society as a whole, we now have relatively small groups operating within their own communication ecosystems. Within these spaces, people repeat and reinforce the same ideas, convincing one another and shielding themselves from differing viewpoints. There’s no dialogue—only polarisation.

Take WhatsApp, for instance. In group chats, people talk only to each other, encouraging and pushing one another toward more extreme views. These closed circles intensify others’ positions rather than invite conversation or understanding.

Social media and messaging apps can spread falsehoods incredibly fast.

Years ago, the internet helped social movements gain traction—like the Zapatistas in Mexico in 1994, or the Catalan independence movement. Now, those same tools are used to radicalise people and reinforce echo chambers. The tide has turned.

What can civil society do about it?

Xavier Giró: It’s important to remember that civil society consists of those who are both organised and mobilised—because many people remain unmobilised, and some could be engaged if they were supported and saw a meaningful reason to do so. This is a key question: if you don’t see a horizon or believe everything is already decided, why would you mobilise?

At present, there is a widespread sense that the usual systems leave little room for alternatives. While movements like the one against climate change—our biggest threat—still exist, they have somewhat faded from the spotlight, overshadowed by the immediate threat posed by Trump and his allies.

It’s not only about Trump, though. Just recently, the Israeli military attacked nuclear plants, scientists, and military sites in Iran across 17 locations. Yet, hardly anything happens in response—only a few protests or threats to sever relations. This reality reinforces the brutal law of the strongest, which is extremely dangerous.

It creates a mindset that if you’re not on their side, you will be defeated or invaded. This leads to increasing militarisation and rearmament, with governments investing heavily in weapons and military industries instead of choosing to build trust. They rely on deterrence through fear rather than fostering trust. Fear has become enormous.

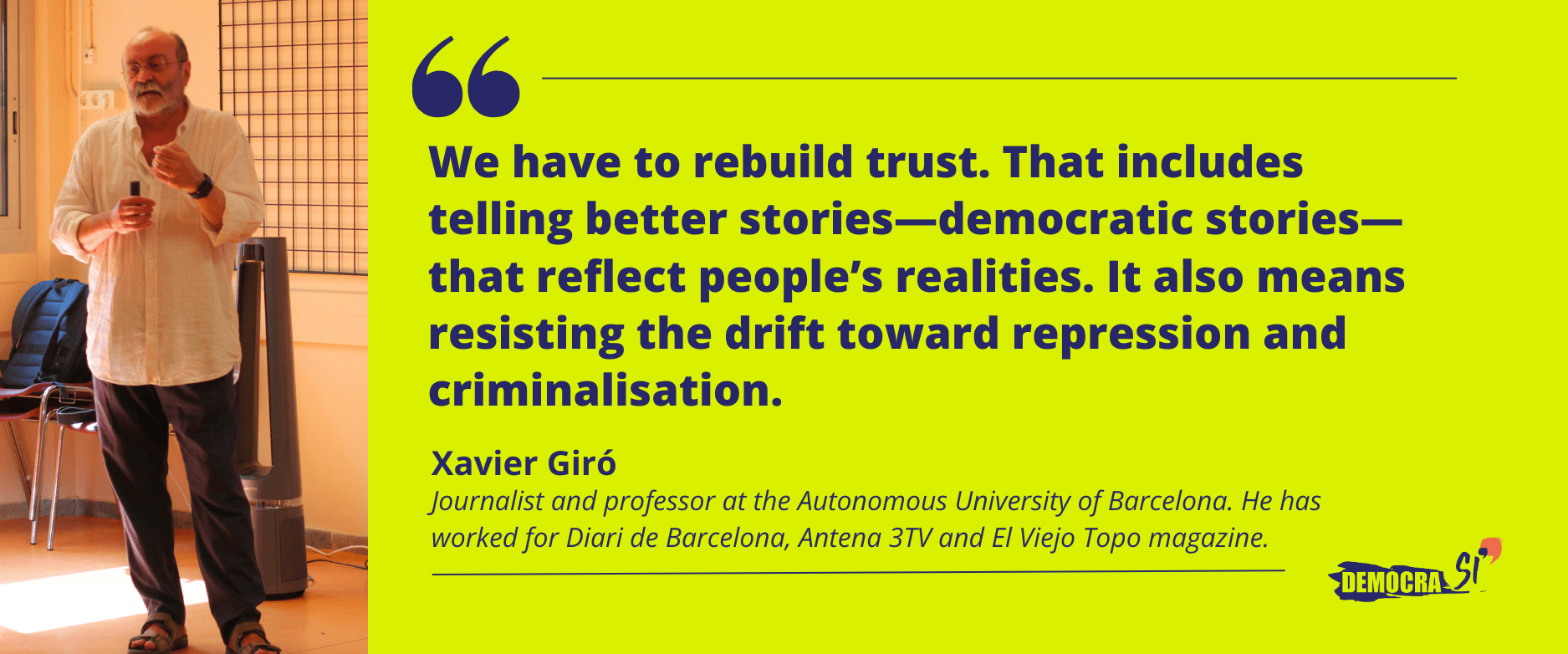

We have to rebuild trust. That includes telling better stories—democratic stories—that reflect people’s realities. It also means resisting the drift toward repression and criminalisation. Most people in prison in Spain are there because of poverty, not because they’re inherently criminal. Society must offer social solutions, not just punitive ones.

Could you give a practical example of how civil society has been successful in countering the challenges?

Xavier Giró: One example comes from a town just outside Barcelona—a fairly large town, with over 50,000 inhabitants. Several years ago, the far right achieved strong results in the local elections there. In response, a group of organised citizens—mostly young and middle-aged people—formed an anti-fascist group.

Instead of relying on the internet, Twitter, Facebook, or other digital platforms, they chose a more personal approach. They went door to door, speaking directly with neighbours. They distributed simple, one-page leaflets that countered the far-right narrative. The message was clear: it’s not true that our neighbours from Morocco or Latin America are to blame for our problems. The leaflets explained where the real issues came from and offered constructive alternatives.

By the next election, the far-right party had lost all traction and failed completely. This group succeeded because they stepped away from the standard methods of communication and engaged people face-to-face.

About Xavier Giró

Xavier Giró is a journalist and a professor at the Autonomous University of Barcelona. He has worked for Diari de Barcelona, Antena 3TV and El Viejo Topo magazine. As a scholar, he has focused on media ethics, political discourse, and how journalists represent conflict and diversity. In 2024, he received the Ramon Barnils Honorary Award for his commitment to responsible journalism and human rights. Xavier Giró is one of the expert speakers and the “Democra-SI” seminar.

About the “Democra-SI” project

Democracy is facing global challenges, with many young people feeling disconnected from political processes. To address this, Citizen OS joined the Erasmus+ “Democra-SI” project alongside 22 partners from 12 different countries. Coordinated by Nexes Interculturals (Spain), together, they are working to explore and amplify inclusive, democratic narratives—especially those that can counter growing anti-democratic sentiment across Europe.

Learn more about Erasmus+ and take action to support democratic participation now!